Kelly at Big A little a refers to an article in the Washington Post by Valerie Strauss, “Assigned Books Often Are a Few Sizes Too Big.” I began to write a comment on her blog, but realized I had too much to say so decided to post here instead. Basically I am highly annoyed by the piece because it conflates a range of methods and situations around classroom teaching of reading and literature in a way that only creates more confusion about an already confusing situation.

Strauss begins by noting that “If adults liked to read books that were exceedingly difficult, they’d all be reading Proust.” Okay, there is a HUGE difference between books that are studied in school and books that are read independently. And when it comes to “assigned reading” there are a million different ways this happens in elementary-college classrooms (despite implications to the contrary in the article). Does she mean books taught in class? Books read in a reading workshop classroom? Read in literature circles? Or a book read together in class? Read aloud and discussed? Each of these are different teaching methods and each requires a different sort of book. One might require books that are easier for kids to read alone while another might be just the place for a book that is harder.

At one point Strauss suggests these books are being assigned without adequate teacher support, at another that they are being taught before kids are ready for them, and still elsewhere that it is about assigning books that don’t speak to child readers. She lumps together elementary, middle school, high school, and college teaching and learning. This is a VAST range of pedagogies, learning styles, levels and more that she is reducing into one clump.

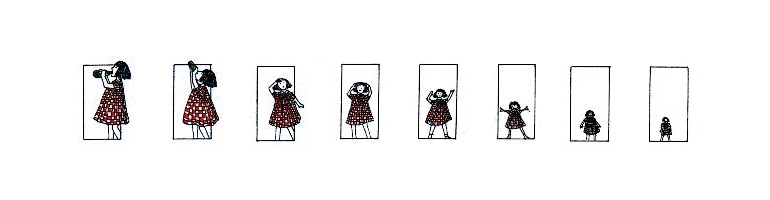

Most of all I’m troubled by her generalization (boy do I hate generalizations) that students are given material that is too hard for them. One of the bedrock ideas of my personal pedagogy is Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, which he described as “… the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” (Vygotsky, Mind and Society, 1978.) That is, I guide my students through readings that would be perhaps a tad too challenging for them on their own. So the idea that teachers shouldn’t do this, shouldn’t assign books that need support, that are a bit beyond their students’ comfort levels disturbs me greatly. This is such an exciting way to both teach and learn. This is how we learn to appreciate literature, to dig deep into it, to learn how to read, really ,really, really read!

Strauss writes, “And elementary schools sometimes ask students to read books such as The Bridge to Terabithia, with themes about death and gender roles that librarians say are better suited for older children.” My response is: What? That book is perfectly suitable for 5th and 6th graders to read with their teachers. Alone, of course not, but assigned to read and discuss and work through with a teacher? Of course!

Then there she quotes Lucy Calkins, “Teachers studied The Great Gatsby in college and then want to teach that book because they have smart things to say about it, and they teach it in high school,” Calkins said. “Then schools want to get their middle school kids ready for high school so they teach them The Catcher in the Rye. It’s a whole cultural thing.” Sorry, but I studied (an important word here) The Great Gatsby in 11th grade and had a great time doing so. My teacher wasn’t amazing by any means, but he did enough to engage us with this book. As for The Catcher in the Rye, I can certainly see it in middle school, again with a teacher guiding the kids. Now they may find it dated and have other reasons for not engaging with it, but I can’t see it being too hard for them if they are studying (yes, studying) it with their teacher in a Vygotsky-way.

Writes Strauss, “Many teachers exclude graphic novels and comics from reading lists, even though a graphic novel was nominated for the National Book Award this year. And Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, has said he learned to read through comics after his schoolmaster father disregarded others who said they would lead to no good.” Hold on here. What sort of reading lists is Strauss referring to here? Assigned reading where the books are STUDIED, discussed, and so forth? Assigned reading kids are doing independently? Again, these are all very different sorts of ways to engaged with literature in the classroom. Besides, graphic novels are a relatively new development and teachers are only beginning to explore them. Give them a break for goodness sakes!

She ends her piece, “So should kids read Shakespeare or the comics? Graphic novels or To Kill a Mockingbird? Reading experts say they should read everything — when they are ready to understand what they are reading.” I agree, but evidently I have a different idea of what “ready to understand” and “assigned reading” means from Strauss’s.

Grrr….there are problems indeed about teaching and learning, but simplistic articles about ‘assigned” reading like this one do nothing to inform and help those outside of schools better understand the problems.

Thanks, Monica, you say it well. It matters more “how” you teach than “what,” often. And the kind of individual attention you and I could give our students, in small classes, allows students to get the help they need to stretch themselves to that zone of proximal development.

I was appalled by her examples, but I think there is some truth to the generalization that children are often asked to read books that are beyond them. In the elementary schools there are many reasons for this, including pressure from parents and children themselves who don’t want to be seen reading a “baby” book, who look carefully at the reading level publishers have assigned, who never want to take a second look at something they knew earlier. And high school English curricula are notoriously full of adult reading material when, as we both know, there is so much good YA literature out there to choose from. What a shame for kids to struggle when they could be enjoying their books.

LikeLike

Very, very good points. Thanks for posting!

LikeLike

Well-put.

I started reading at an extremely young age, and I picked up classic books and difficult novels of my own volition. I often had already read the books we discussed in school. If not, we had the book at home, and I used our lovely, loved, beaten-up, if-books-could-talk copy rather than the class version.

The Great Gatsby is one of my favorite novels. I first read it in high school.

I encourage kids and adults to reach – to challenge themselves – to read what interests them – to read what their kids are reading – to read, period, because cultivating and promoting the love of reading is the most important thing.

LikeLike

I first read The Great Gatsby in junior high school, on my own. Hey, I was bored, I’d heard of it, I saw it on a library cart…

It was a waste of time. I didn’t have the experience or the emotional chops to understand it. When I reread the book years later, after college, I enjoyed it a lot more. I probably would have at least understood more had I read it in high school. So I can sympathize with the concept of books being assigned before students are ready for them.

But I certainly wasn’t harmed by the experience. And I had no one to blame but myself.

LikeLike

If this writer can supply concrete evidence of ONE middle school anywhere in the country that recommends Beloved as independent reading for all students, I will eat my hat.

LikeLike

I’d rather elementary schools assign books with themes like death and gender roles than leave it to TV and films to provide the ‘teaching’.

LikeLike