In the past year there have been some interesting discussions about nonfiction books that seem like fiction (e.g. Steve Sheinken’s Bomb) and fiction books that seem like nonfiction (e.g. Vaunda Micheaux Nelson’s No Crystal Stair). The one this week on the child_lit list serve (about how to identify books like Nelson’s) prompted me to write the following response:

… I’ve been thinking about how children take in history for many, many years (written some books and articles about this) and the issues of authenticity and authority are complicated. I’ve seen errors in nonfiction books that were highly lauded, that appear to be absolutely perfect, only because I was an expert on the subjects. As you note, writers of history have to shape and consider what to include and what to leave out so the act is not as pristine as may be thought.

I’ve just read Andrea Cheng’s ETCHED IN CLAY: THE LIFE OF DAVE, ENSLAVED POTTER AND POET, a fictionalized, multi-voiced, poetic exploration of what this enigmatic artist’s life (there is so little firsthand material about him) might have been like. Kirkus gave it a star and describes it as “verse biography.” I see it as belonging in the same area as Nelson’s book, another fictionalized biography.

A few weeks ago I attended a session about nonfiction for children at the New York Public Library. One of the issues that came up was how to make these stories engaging and accessible for young readers. One author spoke of fictionalizing one aspect in her otherwise nonfiction book and writing about this in the back matter as a solution. Another panelist said she would not have done this, feeling a nonfiction book should be only nonfiction, I’m guessing. Illustration came up too — an artist in one case had to imagine a significant person in a picture book biography because she was unable to find any images of her.

These stories and others just make me think again and again that the telling of history is not something that can be firmly one thing or another. There are reasons to fictionalized true stories in ways that aren’t those of the historical fiction novelist. The novelist is firstly telling a story that happens to be set in the past. The story is front and center. Dickens’ A TALE OF TWO CITIES is firstly a heartrending story; I don’t think we expect to learn a whole lot about the French Revolution reading it. But others are writing about historical situations that they want known most of all. That these lightly fictionalized works end up being in the same category as works like Dickens’ seems very odd to me. (I guess this goes way back to me railing against the use of historical fiction to engage kids in history — way, way, way back on this list:)

And I’ve got a dog in this fight. Like Nelson and Cheng I wanted to get a person’s story out, someone for whom firsthand information is limited (Sarah Margru Kinson, a child on the Amistad). I tried for many years to write it as nonfiction, but the editors I worked with felt the individual always seemed too distant for the child readers and so, with enormous trepidation, I crossed the border to fiction. I suppose it will now be termed historical fiction, but I’m uncomfortable with that because the story is still as true as I could make it and I want children to know that. I don’t see them engaging with the book as they would a work of fiction, but more as a true story. Possibly like readers will with Nelson and Cheng’s works.

It seems to me that these stories need to get out there to children. That the historical record is slanted toward those in power, that the lack of the significant source trail that we require and demand should not be obstacles in getting these stories out there. When it comes to those enslaved from Africa we see a limited number of stories over and over because those are the ones for which there are records and sources. But there has to be a way to get more stories out there and it may be we have to look at that funny place between fact and fiction as one place to do it.

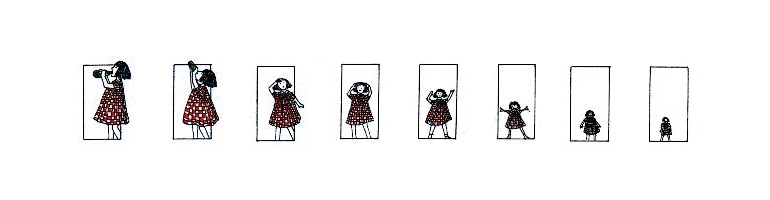

I think design adds to the confusion over No Crystal Stair a bit. With its large trim size and highly visual presentation, it looks the way we’ve come to expect nonfiction for young people to look. If it had the exact same text but looked more like most YA novels, I think it would be shelved with them more often.

LikeLike

I can see what you mean, but I do feel the cover and Christie’s art help to point to the fictional side of this storytelling.

LikeLike

I’m a historian and teach at the college level, and these are concerns that exist throughout the historical profession. There are theorists that insist that “nonfiction” history is really just historical fiction with footnotes. I wouldn’t go that far, but every act of choosing facts and details, sifting evidence, choosing sources, imposing a narrative on a messy set of facts that a historian takes (and to write history is to do all those things) are interpretive acts that inevitably distort the story we tell. There are a number of books that really push those boundaries: I love to assign Richard Wunderli’s Peasant Fires, which opens up one chapter with the text of a sermon, then admits that he invented the whole thing, but explains how he did so. It inevitably provokes a lively discussion about whether or not it is acceptable practice.

And plenty of historians do assign novels to our students because we think they communicate a time or experience better than a work of nonfiction can: a lot of African history survey classes assign Things Fall Apart, for example. So your call for works of fiction deeply grounded in historical research as ways to provide stories that couldn’t otherwise be told is a reasonable one.

It is, however, one that is likely to open up all kinds of debates, as well. There have been interesting debates over, say, Catherine, Called Birdy. Is it too rosy a picture of the likely treatment of a girl who was so disobedient? What are the limits of our ability to imagine the lives and thoughts of people from the past, particularly the distant past?

And don’t be so dismissive of the power of books (and movies) set in the past, even those not trying to be accurate representations, to shape our perceptions of the past. Most people’s picture of Puritan New England is still profoundly shaped by a bunch of works of fiction (especially Nathaniel Hawthorne). Even A Tale of Two Cities strongly colors a lot of the public understanding of the Terror- in that the images created by them keep being perpetuated.

LikeLike

Just to clarify, my comment about historical fiction was a reference to previous discussions on child_lit where some argued that history is inherently boring and that it requires fiction to get kids in classrooms interested (on their own is a different story). Since I think history is fascinating, I don’t at all agree with that view and think that there are many ways for teachers to get kids engaged and excited about history using real stories and real primary sources. The idea that you need the sugar of fiction to get the bitter facts down is not something I agree with. And I sure hope I didn’t come across as “dismissive” as I certainly respect what others do even when I don’t agree with them.

And while I don’t think it is the way to go to get kids engaged, I’m not adverse at all to the use of historical fiction within a larger historical study. For example, I use Lasky’s Dear America book where she does a beautiful job imagining a young girl’s Mayflower experience. We do an indepth study of the Pilgrims and I expose my students to both Mourt’s Relation and Bradford’s memoir so they are excited to see how Lasky uses them so effectively in her work of fiction. It then becomes a great model for them to write their own stories. We also use the film Desperate Crossing, a docudrama about the Pilgrims.

Finally, I think there is a difference is teaching children and college students. My students are at a very different developmental place than yours. And that has to be factored in when considered how they think historically, what previous knowledge and experience they bring to their studies, and so forth.

LikeLike

To clarify myself: I wasn’t trying to suggest that you follow my practices in the classroom- my students find them difficult. Rather, I was pointing out that the discussions I’ve been seeing within the world of children’s literature about history and historical fiction are ones that are being wrestled with at many different levels. And that the messiness of the boundaries that you’re calling attention to and the “in-between” works you’re calling for are things that absolutely should be embraced as valuable teaching tools.

And what I read as “dismissive”-which might have been the wrong word- was your suggestion that we “don’t expect to learn much about the French Revolution” from a work like A Tale of Two CIties. I’d argue that EVERY representation of the past ends up shaping our view of the past, whether it’s intended to be an accurate representation of it or not. There’s a continuum of attempt at accuracy, sure. But it’s really hard to remove Madame Defarge from the crowd at the guillotine even when you know she never existed.

LikeLike

Sounds like we are on the same page then! Related to this discussion is a fascinating article in today’s New York Times focusing on the same issue in film, “Confronting the Fact of Fiction and the Fiction of Fact.”

LikeLike

Years ago I wrote a picture book about the Titanic for Random House (was a mass market variety–a pictureback I think they called it) and it came out about a year after the move, so the kids in elementary schools (kind of to my chagrin) were all watching the movie at home. And at every school visit they’d say something about Jack and Rose, and I’d explain that they were made up people, but much in the movie was true. The kids were indignant most of the time! Of course because it was a movie nobody stopped and said, Hey kids, these folks are made up, but all of this other stuff really happened. Fortunately we get to do that in books. I think I am on the same page as both of you, Monica and Dan. Kids can and should learn about history in different ways. My bias, as Monica knows, is that if it’s nonfiction x you do your best to make everything true. And if it’s a mix, please let your readers know what is true and what isn’t. (As in, yes we my illustrator just could not find a photo of the nanny, but we know she existed, so she did her best and owned up to it in the illustrator notes.)

LikeLike

I meant movie, sorry. Writing too fast!

LikeLike