I really appreciate Julie Danielson’s Kirkus blog post, “The Stories In Between” as she considers a topic near and dear to me — the blurry line between certain works of fiction and nonfiction. Two picture books she considers are Greg Pizzoli’s nonfiction Tricky Vic and Deborah Hopkinson’s Beatrix Potter & the Unfortunate Tale of a Borrowed Guinea Pig. These are both works of history, something of particular interest to me. Julie refers to the following comment I made on a 2014 blog post of Betsy Bird‘s about invented dialog in picture book biographies:

… As you know I tried for years to write the story of Sarah Margru Kinson as nonfiction and finally was convinced to fictionalize it. The result is being called historical fiction, but it hardly is a novel in the conventional sense. I think it is a lot closer to some of the titles you cite here.

I’d love to see some sort of new genre that encompasses books like this, those that have fictional elements, but are based on true events and people. One of the reasons I feel so strongly about this is that I feel it will bring many more people to young readers’ attention. So many people did not leave the sort of paper trails needed to create a full work of nonfiction. As a result they are often not the subject of books for children and/or the same set of personalities get repeated attention. Additionally, the ones we need out there are may well be those who were marginalized in their time which is why the paper trail isn’t there. So if we were more open to books that stand on that fiction/nonfiction border and do so honestly and openly we’d have more diverse voices and stories.

With the current discussion on diversity and how to present slavery to children in their books, I think my final point about reconsidering or making a new genre in order to bring in more stories is all the more critical.

Really interesting post! When you are trying to bring an historical figure alive for a very young audience, you want that character to speak, to have a voice. Yet, if no letters or diaries written by that person exist, as you said, bring the story alive while being perfectly historically accurate becomes very difficult, if not impossible. Most historical movies and plays invent fictionalized dialogue and also change up the time frame of events to create more dramatic tension.

LikeLike

It is a great topic and graduate programs in “creative nonfiction” seem to muddied the waters.

Buitt I think it is simple. I tell students at visits that when we put words in others’ mouths or thoughts in their heads or put them into scenes we imagine we are writing historical fiction — no matter how closely a story may draw from actual history.

So, for me at least, the line is not fuzzy but very clear. If you can’t cite the source or document it, it’s fiction. My recent nonfiction books have 400+ source notes. And, I tell middle schoolers, we are careful to check those quotes!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very interesting topic. Especially when it comes to memoirs. I love Antoine de St.-Exupéry’s non-fiction work (like “Wind, Sand, and Stars”), but the more I learn about it, the more obvious it is that these works are very creatively licensed autobiography. Though this fuzziness as to his accounting of events doesn’t make them any less beautiful in my mind.

LikeLike

Maybe it is the political season but I find myself wondering who can be entrusted to write on this fuzzy line? If writing nonfiction untethered by references what guides the author?

LikeLike

But there ARE references. Deborah’s book (which is fiction) has back matter including an author’s note, “More about Beatrix Potter,” “Notes and Permissions,” etc. I don’t have Greg’s book (nonfiction) on hand, but I seem to recall excellent back matter as well. My book(fiction) has an author note in which I’m explicit about the fiction/nonfiction aspects, indicates research, etc. My thinking is that these sorts of historical books that are fictional, but closely based on real stuff should certainly have references. I guess I feel that kids who go to read my book expecting a novel are going to be disappointed whereas if they go wanting to learn about this true life story they won’t be (hopefully).

LikeLike

Sounds like the importance of the author’s note is growing in importance as it is used to explain the creative/research process with readers. I wonder about the placement of the author’s note (front matter or back matter) as it relates to the reading experience. Do most youth read these notes before reading the contents of the book?

LikeLike

I suspect kids don’t generally read the notes unless pushed to do so. I wrote an article for the Horn Book’s March 2011 issue about back matter for historical fiction novels. In discussing it over the years there are mixed responses to it. But it seems more prevalent now, for picture books too.

LikeLike

My apologies, I was writing from an airport on my phone – sorry for the typos and poor grammar. – Deborah

LikeLike

I agree that there are times–rare but definitely there–when you get closest to the truth of history with invented dialogue. Mara Rockliff’s book Gingerbread for Liberty is a great example. She did extensive research on a minor Revolutionary War character, and her writing is based on that reserch. There simply weren’t quotes for her to use. But his–obviously–invented line of dialogue, used as a refrain, perfectly encapsulates the truth of what happened and what he did. I don’t know whether it should be shelved with nonfiction, or even whether it should be considered for something like the Sibert, but it’s a great book that shines a light on an overlooked corner of history. And it requires that invented dialogue to do it. So I’m intrigued by your suggestion of a new category.

LikeLike

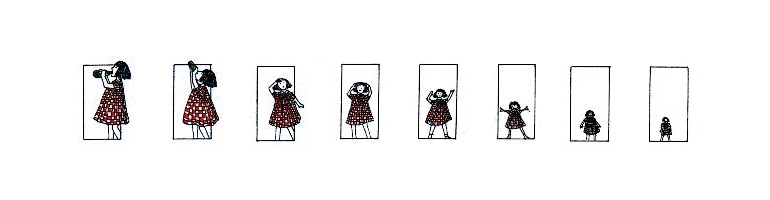

Great discussion! I know it’s hard for teachers and librarians who want a clear line between “true” and “made up,” but I think every historical picture book falls somewhere on a continuum between the two, so I’m not sure whether adding a third category would help.

I haven’t used invented dialogue since Gingerbread for Liberty!, because it’s such a sticking point for lots of people. But one thing I’d really like to see more widely recognized is that picture books have PICTURES, and if it’s a historical picture book, those pictures are more or less fictional. I mean, an illustrator must invent a scene on every spread, with certain people in a certain setting, wearing specific clothes, making specific gestures or expressions, etc. etc. No matter how exhaustively researched the illustrations are, they are still fictional in the exact same way as invented dialogue is fictional.

So…where to shelve historical PBs? I have no idea! But I’ve yet to see one that would meet any strict definition of nonfiction, other than those illustrated exclusively with photographs.

LikeLike

Mara, I totally agree with you about the art. I really appreciated that Salon where the research and thought behind the illustrations were so thoroughly discussed. A bit of a tangent — I think about the reenactments I see in various documentaries, say those of the two Burns brothers. Always wonder why no one seems to comment on them as fiction.

LikeLike

I think you have to be so careful, though. This calls to mind a picture book I read, set in Nazi-occupied Denmark, in which the king bowed to a demand for Jews to wear yellow stars, but he wore a star too, and so did everybody else. It didn’t really happen, but isn’t it inspiring?

More inspiring is the actual history. The Danish government simply refused to force Danish Jews to wear stars. Nobody wore them.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Through the Prairie Garden Gate.

LikeLike