A Monster Calls is a magnificent work — folkloric, allegorical, atmospheric —- a book each reader enters privately and differently. Invited to take-off on an idea by Siobhan Dowd who died before she could do anything with it herself, Patrick Ness has produced a work of magical realism that takes the reader deep into the world of a boy whose mother is dying. Officially publishing in the U. S. tomorrow and beautifully produced with illustrations by Jim Kay, it is an extraordinarily moving reading experience. While Ness lives in the U.K., he is an American citizen and since the book was edited and published in both countries this year, I hope it is eligible for the 2012 Newbery Award. Yes, I think it is that good.

For two teacher friends of mine now in their early thirties, the book had a special resonance. Tyner Gordon lost her mother to breast cancer when she was seven and moved from New Orleans to New York City where she was raised by her aunt. Charlie Felix, a native New Yorker, lost his mother to lupus when he was in the fifth grade. After they read it, they were very eager to discuss the book with me. Afterwards I organized their comments and sent them to Patrick Ness who responded with his own thoughts. And so here is a very profound conversation about a very profound book. My great thanks to all for their contributions to this.

FAMILARITY

Tyner: I found it an enormously compelling piece of work, partly because these situations were so familiar to me. Stomach-churning familiar, almost “Why am I doing this?” again familiar. The anxiety that Ness wrote about is one I knew so well when this happened to me. And so I wanted to see how Conor would deal with the same thing I dealt with.

Patrick: Familiarity is a fascinating idea and one that was really, really important to me in the book. Because, to some degree, we’ve all suffered loss, but we’ve all really suffered FEAR of loss. And so everyone has some idea of what it feels like, but it has that horrible trick of making you feel like you’re the only one. For someone like Conor, at 13, that’s incredibly isolating. And just to know that someone else hears him and knows what he’s going through, well, that’s half the battle, isn’t it?

SCHOOL

Charlie: The school sections of the book really resonated, especially the looks from Conor’s peers. When I came back to school after my mother’s death I got a lot of cards, big eyes, and little mouths all day. No one wanted to talk to me and I didn’t want to talk to any of them. Teachers too; they wouldn’t call on me and I stayed as quiet as a piece of paper. Then, a few months after my mother died, this one person who’d been bothering me said something about my mother and I flipped out — picked up a desk and threw it at her. I’d been a quiet kid with no friends and never had done anything like that. So could totally buy into Conor’s explosion. When my fourth teacher from the year before heard what happened she took me to her classroom and let me help. After that she kept sending someone to pick me up and I’d help in her classroom. She didn’t talk about it, just understood I needed space, but someone to be around.

Patrick: School is such an entirely different (and often un-supervised in a very important way) world for a young person. All the rules are different and your role in it is completely different. It was was important to me to get Conor in school and to really try and see, truthfully, what it would be like for him there. It’s hard enough to be different, but what if your difference is something no one wants to talk about? So they don’t talk to you at all? Every young teenager feels invisible at some point, but for Conor it’s like he’s almost completely vanished.

GRANDMOTHERS

Tyner: My grandmother was with us too (although not in a pantsuit!) when my mother died and so I connected very much to Conor’s reactions to his. And so the scene with the clock really resonated with me. When Conor turned the hand I wanted him to do it, perhaps because I’d been too chicken when I was in that situation. Now I can appreciate how my grandmother, like his, was not only dealing with a defiant grandchild, but with the death of her daughter….It is still coming for me, especially this past year with the deaths of my grandmother and great-aunt. I was definitely was reacting more to my grandmother’s passing. Grandmother was family — holding it all together. She had the memories of my mother, the house, and so forth. Also a loss of another big piece of New Orleans even after all we lost from Katrina. This monster is still very pertinent for me.

Patrick: Because of the folkloric feeling that runs as a current through the book, it was really important to me to have an utterly non-fairytale-like grandmother. All business, a professional woman, brisk and smart and full of energy, and who I always imagined has been secretly exasperated (in a loving way) by her much more relaxed daughter. And so to Conor, she’s practically an alien and not sympathetic at all. But I think – and hope – that we see more than Conor does. That this threat of loss is hers as well, and she’s dealing with it the only way she knows. Plus, she’s funny. She makes me laugh, in a way that Conor won’t get until he’s much older.

FATHERS

Tyner: I was disgusted with the father, especially when he would discuss his wife. Some of this may be compared to my father who was a slave not to a woman, but to drugs. He left when my mother was diagnosed and wasn’t able to come back when she died. I found out later that he had no intention of taking me and, in fact, signed over custody days after my mother died. Not knowing that, like Conor, I begged to go live with him and got the same reaction Conor got. My father, like his, was a weak man who could have been such a help and was a dead-end.

Charlie: My father, having another family, had no intention of taking care of me. So my response to Conor’s situation was “Why doesn’t this father love him enough to take him?”

Patrick: My take on Conor’s father is that he’s not a bad man at all, he’s just weak, right at the moment that Conor needs him to be strong. It was important to me to, again, try to tell the truth about this. Life doesn’t always give you the storybook ending. In fact, hardly ever. But that doesn’t mean that happiness and hope and love aren’t also possible.

JEALOUSY, FAIRNESS, AND ANGER

Tyner: I felt a little jealous of Conor. That is, he was able to get clarity at the end. I got it all, but much later.

Charlie: You are taught when you go into hospital you get better. I never thought my mother was going to pass away. She passed in the hospital. So reading about Conor’s mother getting treatment felt it wasn’t fair. So I ended up angry at Conor. My mom’s passing, going to a dark place, going to the street, and then this is how you don’t die even with people dying around. Wouldn’t have gone to the street if my mom hadn’t died.

Patrick: It’s that paradox, isn’t it? In order for a story to be universal, it has to be as specific as you can make it. A Monster Calls, to me, is only secondarily a book about the issues of loss and grief and hope. It’s primarily a story about Conor and his very specific experiences. I couldn’t begin to describe the experiences of every child who’s gone through this – and what an awful, shallow book that would have been – I can only talk about Conor. He’s lucky in some respects, because the monster comes, after all, but all that is swept away by the possibility of losing his mother. I really think we leave him hopefully, but he does have a long, long way to go. In my heart, I hope he’s out there somewhere, doing brilliantly, I really do.

MONSTERS

Charlie: My fourth grade teacher had appeared to be a monster the year before. If you had a behavioral problem she fixed it by smacking you on the back of your head (she had rings she’d first turned to the back). She also smoked in the classroom. She wore a house dress (the sort of thing women used to wear around the house), red shirt underneath, and slippers so you couldn’t hear her coming; all you’d hear was wind and then she’d be right on top of you. I was scared to death of her, but it turned out she was the one who knew me. When that thing happened, my mom’s death, she became a person. The monster teacher became a person just as Conor’s monster was a person preparing him for something really difficult, letting his mother go in that way.

Tyner: While reading I was thinking, what does this monster represent? I went through the same emotions that Conor did as he heard the stories. Yet each story opened up new ways of thinking for me. I remember having new emotions and new things to think about all the time– double mastectomy, chemo, stitches, and then, after her death, a new city. My New Orleans 2nd grade teacher stayed very close. She gave me a set of Beatrix Potter books before I left and I read all those books over and over and they comforted me. My NYC 3rd grade teacher gave everyone a composition book and it was the first time someone had done this and told me I could write whatever I wanted. I wrote furiously in class. When I filled it up, without saying anything she gave me a new one three times as big, knowing it was my catharsis. Then there was Ms. Gumbs in 5th grade who was no joke and had you quivering. I look at these three ladies as giving me what the monster gave Conor.

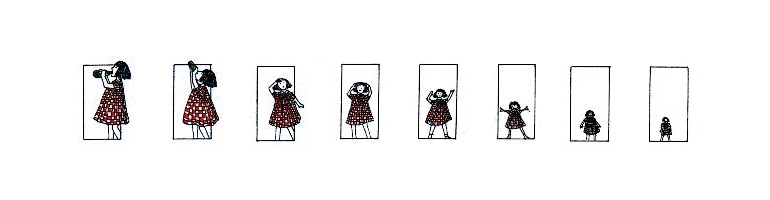

Patrick: I get asked quite a lot about what the monster “means”, and I’m very, very much the kind of writer who doesn’t think pinning a single meaning on it is in any way helpful. That’s kind of the whole thing it tries to get across to Conor, that you’re more than one thing at any given moment, that it’s that complexity that makes you human. For me, the important thing the monster brings is the stories, because – very much especially so for the young – stories are often the one way that feelings and fears for which there are no other words can be dealt with. But there’s a paradox in that, too, in that stories end, but life goes on, and so I think the monster is trying to say to Conor that that’s okay. Monsters are complicated to me, they always have a reason, they always have a story, and they can be helpful and kind while at the same time still scary and monstrous as all hell. Again, complexity. It’s what makes us human.

This is an awesome discussion of the book! I loved the book so much and love this idea for a “review”. Thanks!

LikeLike

Monica, WONDERFUL interviews. Thank you. But I don’t know that I can handle reading this. (I’m sure my kids can. Not sure about me.) I wept just reading this piece!

LikeLike

Marjorie, I’m not generally good with this sort of book myself, but I think it is doable. The folkloric stuff is very very strong. But I think it depends on what you bring to the reading too. I gave it to Tyner (a colleague) because I knew she loved horror, stupidly forgetting her own mother’s death until she told me what a powerful experience the reading had been and that she wanted her fiance Charlie to read it too. Ended up being a worthwhile experience for both as you can see.

LikeLike

I love the conversational format you used. Thank you to Tyner and Charlie for sharing their experiences.

LikeLike

Pingback: An interview with Patrick Ness « The YA YA YAs

Pingback: Thinking Back « Heavy Medal: A Mock Newbery Blog

Pingback: Thoughts on Newbery: My 2012 Druthers | educating alice

Pingback: Battle of the Kids Books: Opinions, not Predictions « Reads for Keeps

Hi there,

I’m doing a paper on the book and I noticed you referenced it as being “allegorical” could you please elaborate on how the text can be interpreted differently to reveal a hidden message?

Many thanks

Tahlia

LikeLike

Pingback: Calling My Monster – Entirely of Possibility